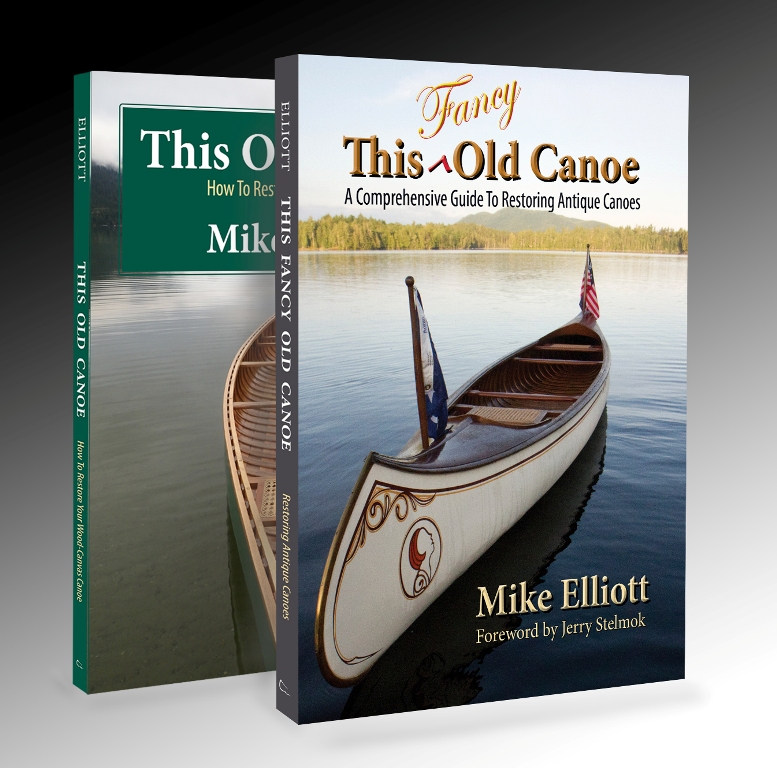

Jerry Stelmok Introduces This Fancy Old Canoe: A Comprehensive Guide To Restoring Antique Canoes

April 19, 2024

by Mike Elliott, Kettle River Canoes

The foreword to This Fancy Old Canoe is written by Jerry Stelmok. Here is his introduction to the book.

In this, Mike Elliott’s second book on canoe restoration, he uses his first book, This Old Canoe, which treats the more commonly encountered types of canoe damage and repair — broken and rotted ribs, planking, gunwales, need for recanvassing, and such — as a springboard to address some of the less common and often more challenging afflictions found in certain antique (and I’ll use Mike’s appropriate term) fancy canoes.

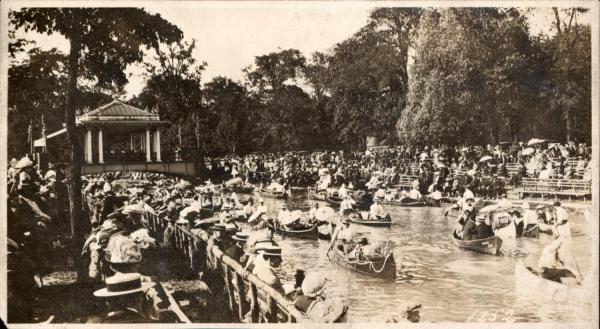

In the late nineteenth and early third of the twentieth centuries, recreational canoeing became very popular. Not just to explore the backcountry but as a social phenomenon giving rise to large-scale urban canoe clubs and liveries. On a Sunday afternoon on rivers such as the Charles in Boston, and the Detroit’s Belle Isle section, hundreds of canoes might be packed cheek by jowl ferrying sociable paddlers decked out in their finest outfits. These flotillas blossomed not only because they were fun and a chance to show off canoes, but also because they were one of the few acceptable activities where a fellow could be accompanied by his special girl unchaperoned — aside from the thousand or so other canoeists in proximity.

As an expression of this high-visibility exposure, the canoeing public began demanding finer, more strikingly adorned canoe models with more “flare.” Not merely fancy paint jobs, but higher, more romantic sheer lines, long decks leading to open cockpits with coamings, pennant holders, etc.

The builders responded. From the 1890s through the 1930s, with great skill and attention to detail, they employed extreme steam-bending of gunwales, stems and decks, to achieve the desired romantic flavor. Among these builders were Robertson, Brodbeck, and Arnold, in the Boston region. In Maine, they included Williams and Heckman in Kennebunk, Morris in Veazie, and Old Town in Old Town.

To make the canoes practically capsize proof, hollow air chambers termed sponsons were installed beneath the gunwales on some models.

All these extraordinary features present challenges that require innovative restoration procedures when they turn up as broken, dry rotted, or missing components in antique canoes to be repaired.

Mike breaks down these issues into various categories. With detailed instructions and clear photographs, he describes how to go about fixing the problems at hand.

It has been said that there’s more than one way to skin a cat. I’ve never skinned a cat, and never plan to. I like cats, although maybe not as much as I do dogs. The point is that, in my years of experience, I don’t necessarily employ the same techniques as Mike does for each task. Nor does the fellow down the road from me, Rollin Thurlow, who has been at canoe building/restoration as long as I have. He has also developed his own skills and methods. (But then, our town of Atkinson, Maine, is just possibly unique in that it has a full-time canoe shop for every 150 residents.) The late great Jack McGreivey of New York, considered by many of us to be the Dean of canoe restoration, had developed his own methods of tackling these challenges, too. Simply put, there is no single correct solution to address these often-complex issues. Mike freely points this out. His own methods are straight-forward and offer directions that, with care and some skill, should lead to success.

An important section of the book that I find very interesting is the restoration and repair of the various all-wood canoes manufactured in the Peterborough-Lakefield region of Ontario. Builders such as Herald and Stephenson, as early as the 1860s, made many types. These differ from the wood and canvas canoes in that their wooden hulls had to be perfectly watertight without a waterproof skin. I have very little knowledge about restoring such canoes, but I have always been impressed with their artisanship and the obvious challenges they present. Mike takes on a few of these himself and widens the book’s scope with excellent contributions from Sam Browning in the UK, who shares his experience restoring these impressive watercraft. Such is the value of the internet in all its forms when it is employed as it was initially intended — for sharing information.

Of course, numerous posts on the various apps and services these days offer advice. Some are excellent and some are sketchy. Some that are dependable are the Forums on the website of the Wooden Canoe Heritage Association (forums.wcha.org).

Still, when confronted with an exquisite courting canoe in need of major restoration; or just a more ordinary canoe that has issues with those unwieldy sponsons, you will find nothing quite as accessible and reassuring as a credible book on your bench. That is why This Fancy Old Canoe can be your best place to start.

Jerry Stelmok

Atkinson, Maine